Wrongdoings in Biomedical Research

The evils of relativism and utilitarianism

Modern codes of bioethics largely arose from the ethical crimes of the past, such as the Tuskegee Experiment and the crimes of the Second World War (WWII). It is imposible to understand the moral knowledge captured in those codes, their depth and scope, if we do not first take into account their origins as a correction of the wrong morality and the consequential misdeeds of the past. We learn only from mistakes; ours’ and others’. We learn costly and forget easily, especially when the wisdom comes from wrongs perpetrated by others. The forgotten knowledge must be re-created time and time again, although we do not start from scratch, we keep building over the shoulder of others.

In this article, I will briefly review crimes committed in the name of medical science and the ethical codes that consequently emerged to prevent those from happening again. I would like to stress the fact that the moral truth is not manifest, that there is not infallible human being nor infallible or definitive code, and that it is not given that mistakes of the past will not be repeated. The codes of ethics, such as the Helsinki declaration and the Belmont report, have no meaning if they are not implemented by practitioners every time an ethical dilema appear.

I will argue that, what we now call crimes or unethical research practices, can been look at as a part of a different frame of ethical principles and values. Yes, it not a lack of ethics; the practices of the Tuskegee Experiment and those of the WWII are rational in the context of a wrong ethic. In this regard, I propose that the two main evils of biomedical research are two moral perspectives: relativism and utilitarianism.

As we will see through the three cases that follow, even the worst criminals can morally justify themselves. Their situation is not that of lack of morality, but a mistaken and corrupt morality that is behind the worst crimes of biomedical research.

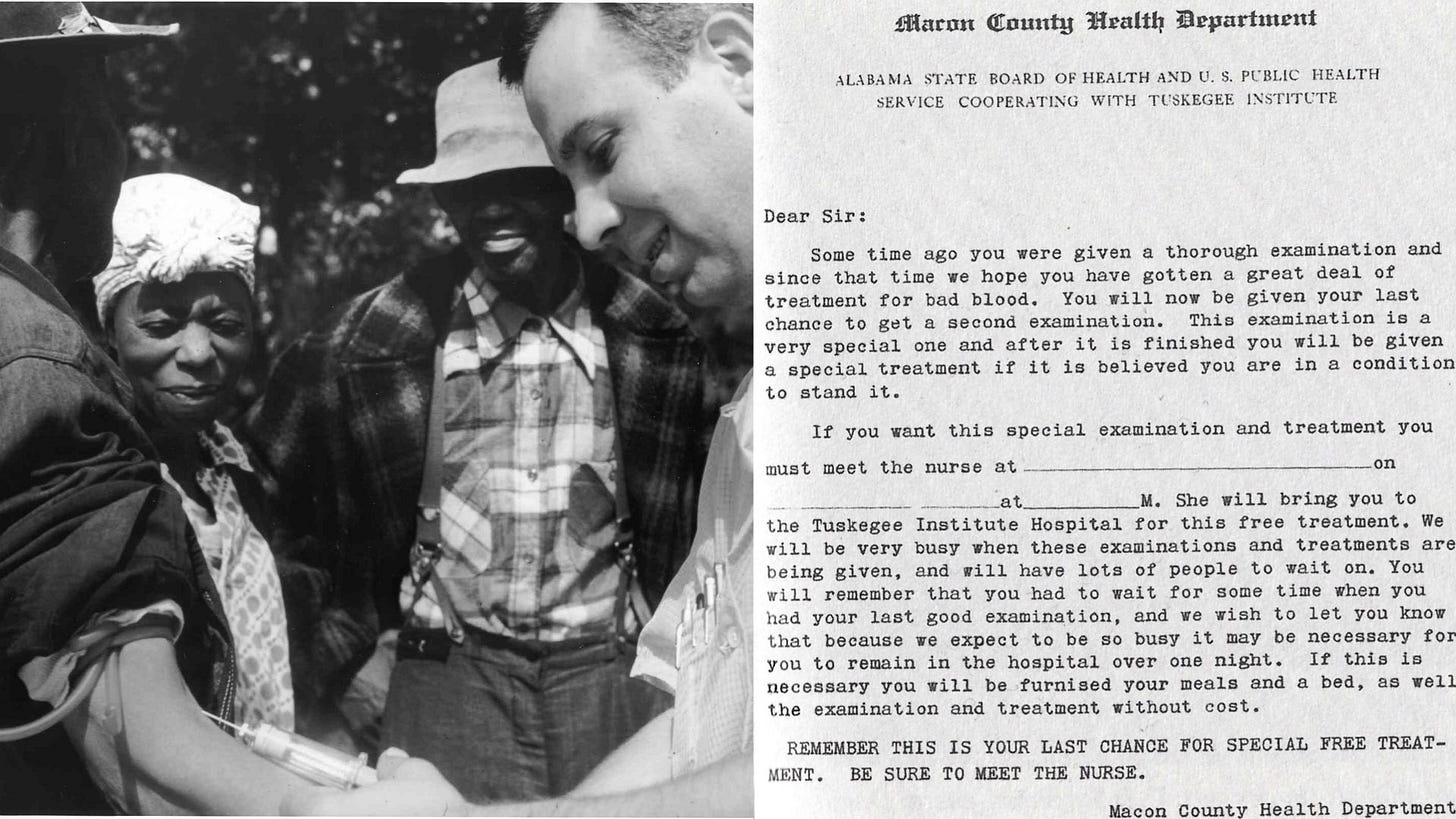

Case 1, Alabama

The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male (informally referred to as the Tuskegee Experiment or Tuskegee Syphilis Study) was a study conducted along 40 years, between 1932 and 1972, by the United States Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on a group of nearly 400 African American men with syphilis. The purpose of the study was to observe the effects of the disease when untreated, though before the end of the study medical advancements meant it was entirely treatable. The men were not informed of the nature of the experiment, nor of that of the disease they suffered, and more than 100 died as a result.

Before started, the participating researchers reflected about the morality of such an experiment in the following terms: Given the living conditions of the studied population, notably the lack of access to modern medicine, they are not likely to receive treatment anyway; the suffering of these men can be used for something good instead to go wasted; to get to know better the natural history of syphilis. That will make for the progress of the medical science and will potentially reduce human suffering in the future.

They made the rational moral decision of deceiving and refusing to help those specially vulnerable individuals for the greatest good of scientific progress.

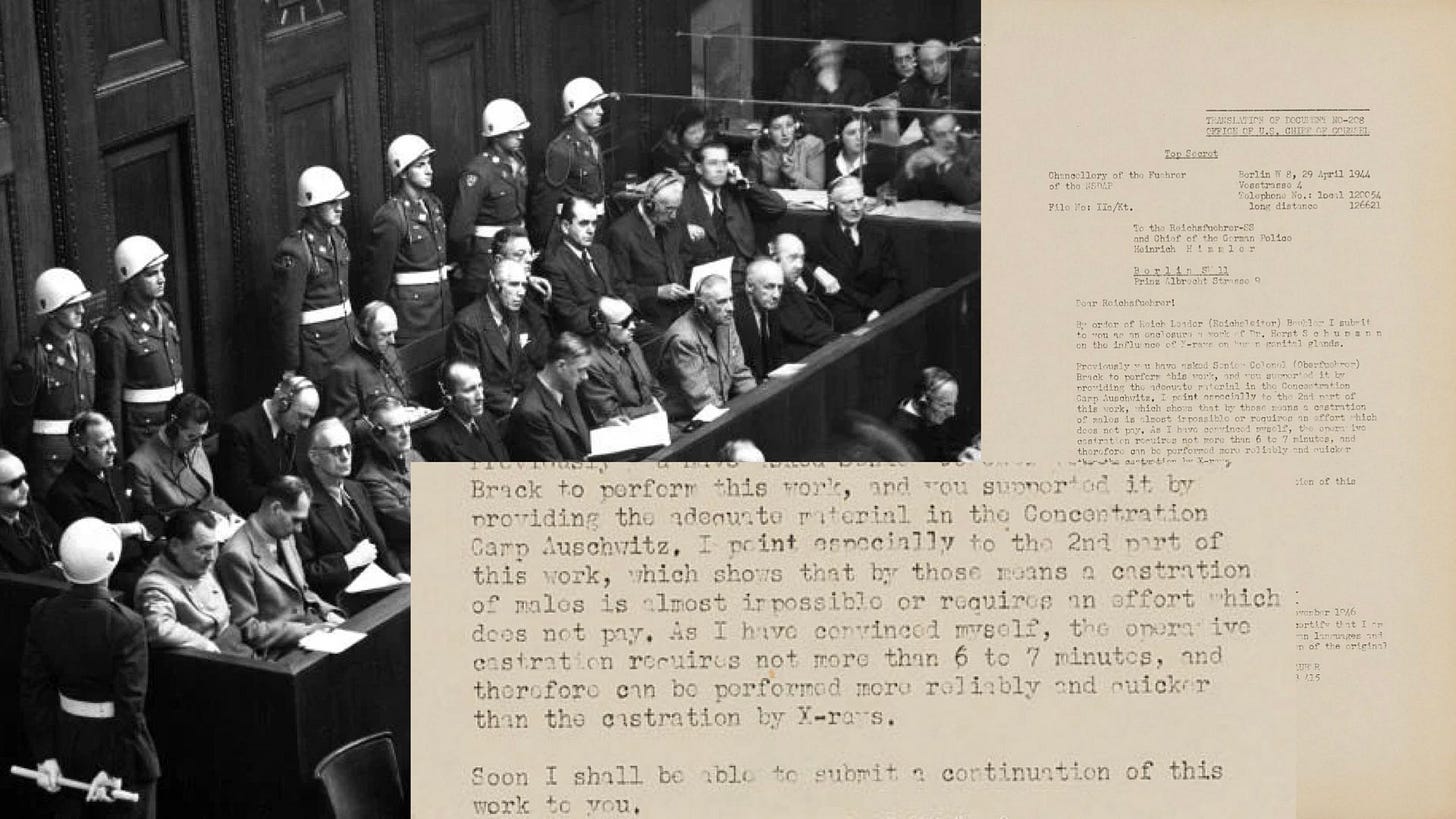

Case 2, Nuremberg

After World War II, the Nuremberg Trials brought many Nazi doctors and scientists to justice for their roles in experiments involving human subjects. Well organised and documented experiment in physiology were performed on war prisoners.

The researchers reflected that they should follow orders of higher authorities and that the decision of eliminating a part of the European population was taken for the greater good of the nation. The situation was considered as an opportunity to push forward the progress of medical sciences. The prisoners are going to die anyway so, their existence can be use for the progress of knowledge.

The trial resulted in the establishment of the Nuremberg Code, a set of principles intended to govern human experimentation that emphasised the importance of voluntary consent and of minimising harm to participants.

Case 3, an Art that must be Preserved

In a post in a social media platform a neurosurgeon wrote: “Surgery can be, and sometimes is, a beautiful thing. The art of clipping a basilar bifurcation aneurism must be preserve. A definitive strait forward, safe, and effective surgery, specially in these narrow necked.”

The post was accompanied by a beautiful picture of the human brain and the circle of Willis together with a short spotless surgical video.

Another colleague replied: “Evidence clearly shows that endovascular treatment is safer in these cases”.

The author of the initial post replied to this: “Yes, but no definitive evidence favour coiling in these cases. More research is needed ”.

A third commentator wrote: “clipping those relative easy cases help future patients. Clipping basilar bifurcation aneurisms is an art that must be preserved”.

The case describes a far more subtle unethical behaviour or, if I may, a clear use of utilitarian arguments to justify a clinical decisions and to initiate research programs. At the same time, this example is more important to us becase affects our current neurosurgical practice. The problem adopts many forms and I finally decide not to quote the surgeons that inspired this case to avoid personal confrontation. I think that I managed to cover every trace of the actual source. However, every resemblance with reality is not a coincidence.

There is no way to know, but I think that our brilliant Neurovascular surgeon reflected as follow: the patient can be treated with coiling, according the the best rational explanation and evidence, or I could clip it with an increased risk of complications, perhaps offering a more “definitive” solution. The clipping has however further advantages; I will progress in my learning curve and teach my fellows and my community, I will push forward the field of Neurovascular surgery. We will use that experiences from now on for the greater good of our patients. All things taken into account, clipping is the best option.

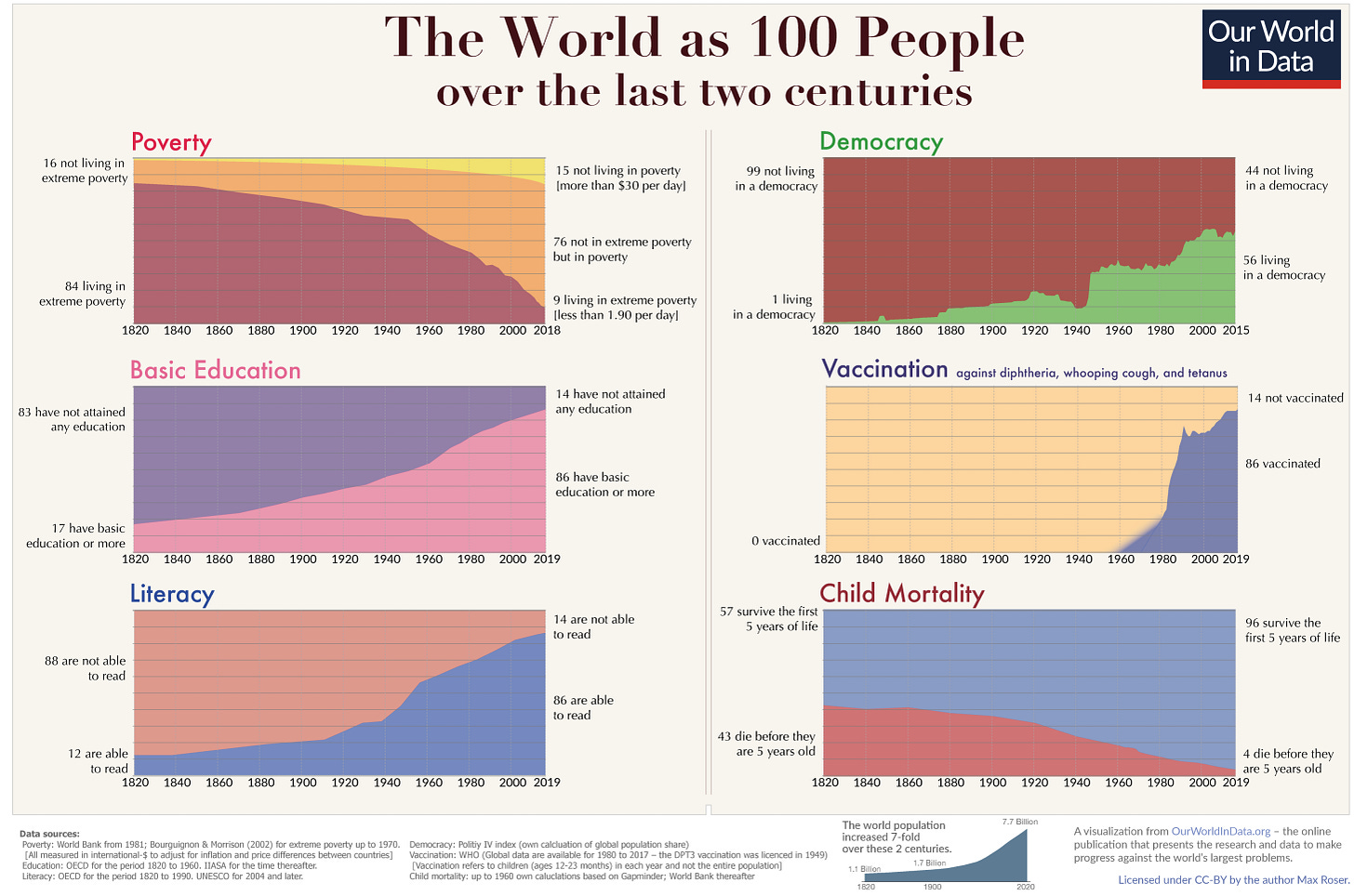

Moral Knowledge

It is perhaps obvious that technical knowledge progresses, it is even clear that it progresses at increasing speed. Wealth grows parallel to innovation. It is less obvious, but equally true, that moral knowledge and practice also progress although at a different speed. Not far ago, in many European cities, people gathered in great numbers to witness and cheer public executions and torture. The practice of inducing suffering and murdering alleged criminals was considered ethically sound. (“We take the kids to watch executions so they learn”). Today, the use of excessive force by a law enforce officers, even when it does not result in personal harm, is considered a moral aberration. That is progress in moral knowledge. It is the idea that the unjustified use of violence against individuals is wrong and worst if enacted by someone in situation of force. As Ben Parker, the uncle of Peter Parker (Spiderman) put it: “with a great power, comes great responsibility”.

Along the history of medicine medical ethical knowledge has progressed. In 1803 British physician Thomas Percival defended the idea that when the doctor’s plans conflicts with the patient’s preference, doctor’s should prevail for the better good of the patient. This idea was incorporated into the first ethics code of the American Medical Association of 1847. In that code it is stated the following under the title: Obligations of Patients to their Physicians; “the obedience of a patient to the prescriptions of his physician should be prompt and implicit. He should never permit his own crude opinions as to their fitness, to influence his attention to them.”

Today the exact opposite is true. Further progress revealed that the principle of autonomy (the rule of respecting patients preferences) should take preponderance. Autonomy is not only recognised in the ethical codes, it is also mandated in the law of many countries.

Physician have produced and adhere to a number of documents containing ideas about what is good and wrong, both in the practice of medicine in general and in innovation and biomedical research in particular. Since time inmemorial, physicians must freely agree on general ideas about what is good and what is not to join the medical profession. This agreement is a necessary condition to become doctor, and it is binding and universal; it has greater reach than local state laws, ideology, religion, or culture.

Having said that, in practice, ethical dilemas do not show themselves in clear forms. Confronted with decisions in specific situations, researchers and doctors usually face the clash between two or more solid ethical principles and they might be not sure about what is best. A patient that refused a procedure that will benefit him or her and others, a vaccine for example. Does autonomy prevail, or beneficence, or maybe justice? Reality is never self-evident or self-explanatory, the truth is not manifest and solutions to ethical problems are difficult to come by. It is a common and fatal mistake to think that moral truth is obvious.

Moral and ethical knowledge are rational, meaning that criticism is accepted and encouraged. That criticism applied to the solution of specific ethical problems in the real world is the only source of moral progress. The aim should be to agree on a good rational explanation for every principle and for every decision taken. There are no definitive moral code, and there will never be, because progress in moral knowledge is unbounded. Moral does not come from emotion, feeling, tradition or religion; but from reason and values applied to solve ethical problems.

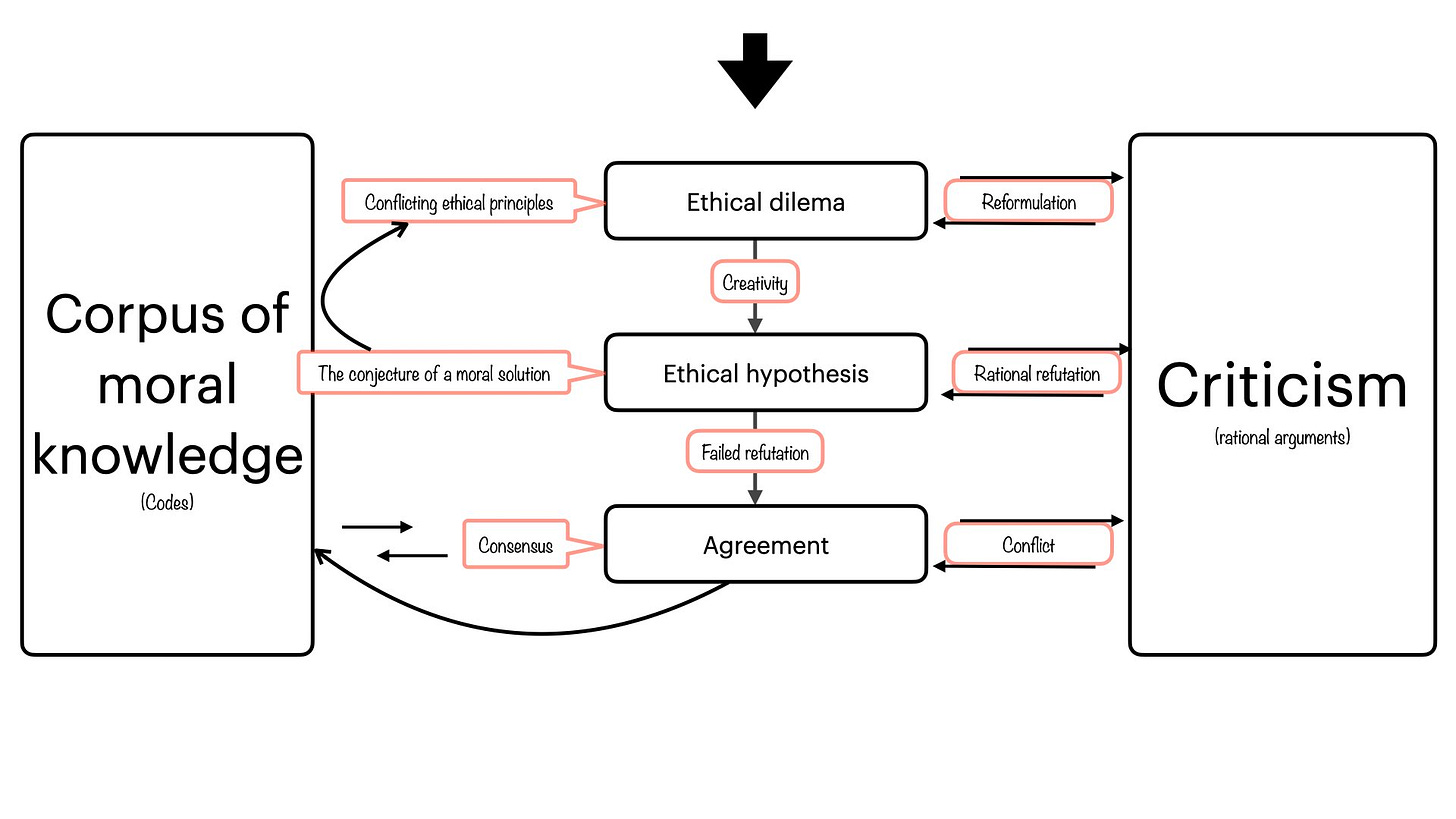

How do we then deal with the dilemas of every day practice and, at the same time, grow moral and ethics knowledge? we do that by solving ethical problems.

Ethical problems

An ethical problem or dilema is a conflict between two or more ideas involving moral matters. Both ideas cannot be true, but also importantly, both can be wrong and a third better one may be created. Given a patient that refuses a potentially life saving treatment; should we respect his or her wish, or should we provide the beneficial treatment despite the patient wishing? That is an ethical problem.

From the point of view of principism (see below) ethical problems arise when two or more overriding principles (autonomy, beneficence, non maleficence, and justice) collide. From this collision or clash of principles, the practitioner must conjecture a solution, a moral hypothesis. This moral conjecture is informed by the ethical codes of the time and controlled by criticism of the most severe type, serious attacks to prove that the solution hypothesised is morally flawed.

Why is severe criticism better than of attempted justification? The answer is methodological. Any conjecture can be easily justified (and any moral wrong), but only the best among them can resist a serious attempt of refutation. It is easy to finds reasons that support one particular moral position, it is difficult to resist attempts to show that the same position is wrong. Same as in science, the best hypothesis are not those that are only supported by some facts, but those that cannot be refuted by known fact or observations. Also in science and in ethics everything can be improved and our best knowledge is only provisionally so.

The space of moral possible solution is much bigger than that reflected by the clash between the four overriding principles. That complexity demands an effort of integration and creativity and that is another reason why the resolution of specific ethical problems are not easy to come by nor can be automated. Ethical solutions in the real life are case specific and involve agreement between stakeholders and the respect of the written rules. The agreement is not reached when the solution is justified, but when no better solution can be found.

Ethics and Religion

Ethics and religion has mistakenly been mixed in the bioethical literature as if they were the same thing. The ethical code of the American Association of Medicine of 1987 starts as follows: “Medical ethics, as a branch of general ethics, must rest on the basis of religion and morality”. The idea that ethical principles should be altered in the light of the religion that the person professes is often smuggled into ethical discussions. That is one of the ways in which relativistic ideas are advanced into the field. It is assumed that a different set of values according to different religions must guide the resolution of ethical dilemas in medicine.

Religion is a matter of faith and a feeling described as espiritual emotion. Religion is also a set of dogmas that transcend the subjective experience of the individual to conform rules for living in society. Religion is not necessary rational in this foundational sense, although there are many reasons with considerable amounts of explicit and implicit moral knowledge built upon faith, espiritual emotion, and cultural tradition. The ten commandments of the Old Testament (the Torah) is a good example of ethico-legal code. It is undeniable that current values and moral knowledge are rooted in the dogmas of religion. These ancient texts collected a set of genuine moral knowledge together with the rule that prevents it to change, to progress. Dogmatism, the idea of a definitive uncriticisable truth, the inability to improve, is the unreconcilable separation between biomedical ethics and religion.

Biomedical ethics plays in a different arena. It does not depend on faith or spiritual emotion but in moral values and reason, it is anti-dogmatic. It is open to criticism and is based upon explanations about why a certain decision is taken and not the other, or why a given principle takes preponderance over another when they conflict in ethical dilemas.

While any change in the content of the Bible and other holy books are strictly forbidden, the set of ethical codes such as the Helsinki declaration, the Belmont report are constantly opened for modification and criticism. To be fare with religions, there is something that change when moral knowledge advance in society, the interpretation of the religious dogmas. For example, taken literally, the Ten Commandments declare women a propriety of men, but it is difficult to find religious people that do not think that humans cannot be own. Individual freedom and equality before law is accepted without contradiction with the Commandments thanks to the so call interpretations.

No matter the religion a doctor or a patient profess (or the lack of it) the resolution of ethical dilemas affecting them should be based on the same set of ethical principles; biomedical ethical principles are thus universal.

What about the diversity of human culture around the globe?

Diversity is sometimes misunderstood as diversity of ethical principles.

Should the same ethical principles be applied to every person despite of his or her culture, country, or religion?

Although no everybody agree, I want to be categorical here: yes, they should. The same ethical principles apply to every single human being in the world, despite their religion, culture, gender, believes, race, etcetera.

In biomedical ethics, diversity is honoured through the principle of autonomy and justice. Individuals have agency to decide according to their own ideas including religious, cultural or of any other sort. The principle of justice also come in helps to respect diversity since physicians and researchers are bind to be fair with every patient without undue discrimination for reason of gender, origin, political orientation, etc.

Ethical considerations in clinical practice, innovation, and research

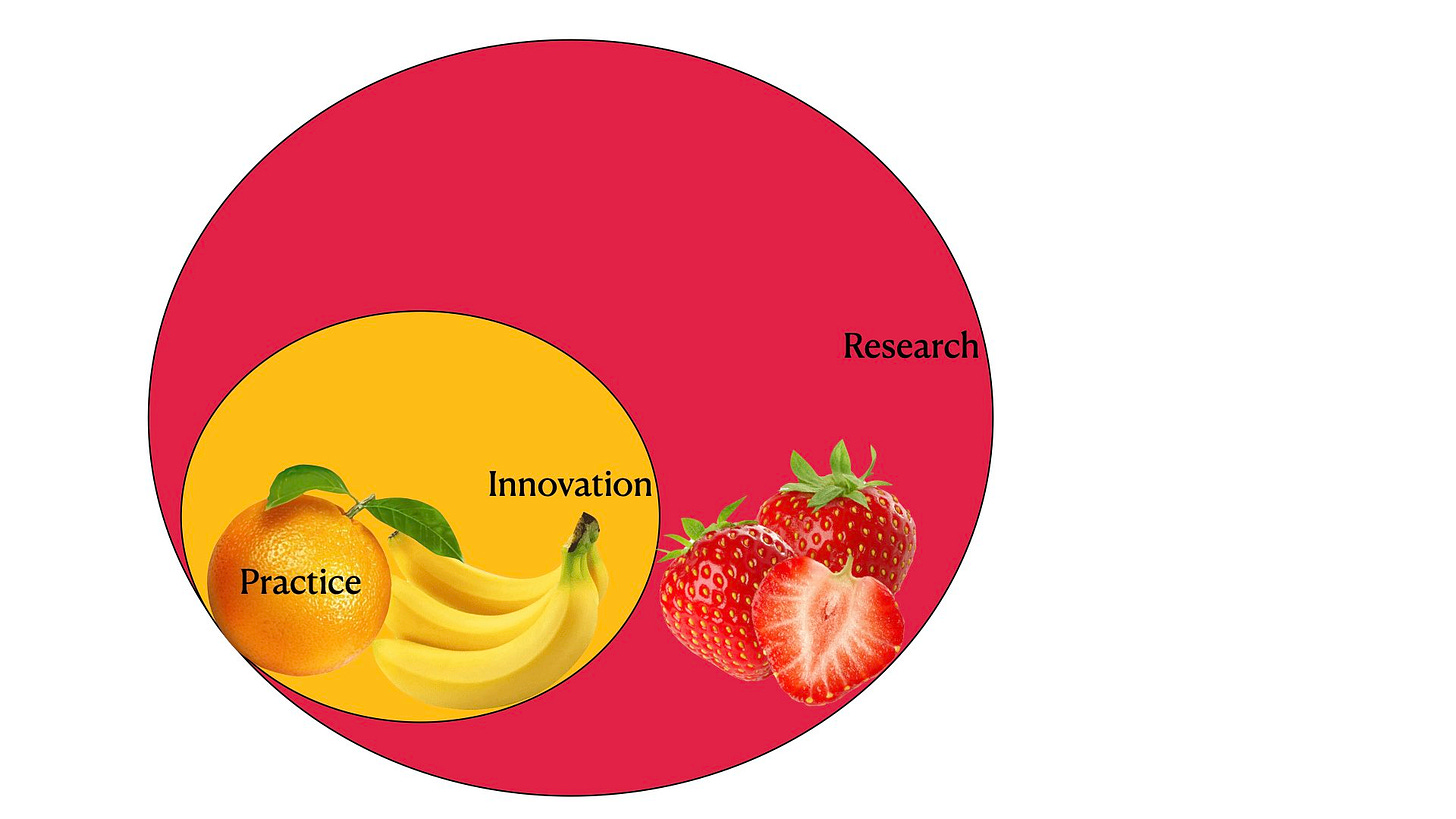

There are at least three different scenarios where ethics conflicts play: Clinical practice, which is about helping people with health problems; innovation which about improving the practice, or research which is about growing medical knowledge. We might consider also prevention and promotion of health as different scenarios involving ethical decisions, but they won’t be discussed here.

In practice, it is not always easy to distinguish those three areas; practice, innovation, and research. For example, is the inclusion of a new bipolar forceps innovation or is it regular practise? Is the incorporation of ultrasonography into the surgery for brain tumours innovation or research?

From the ethico-legal point of view, clinical practice, innovation, and research are related in the following way: practice is informed by the core bioethical principles (autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice), innovation adds its own ethical considerations (especial consent requirement, innovation committee review, etc); finally, over those, research must comply with additional principles and more oversight (see Helsinki declaration). In other words, studies including human subjects (or data about them) must comply and respect the specifics codes for research as well as those referring to innovation and practice.

Ethics in clinical practice

Clinicians have a very simple, readily available, and easy to use toolbox to address ethical dilemas of everyday practice; the four overriding principles: autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice

Principism is a simplistic but useful system of ethical analysis derived from four overriding principles of ethics. The four principles referred here are non-hierarchical, there is no moral priority of one over another. To solve a give ethical problem, anyone of the four could potentially take preponderance.

Autonomy

Autonomy is founded in the deep respect for individual freedom and the intrinsic value of the life of the person. According to the ethical principle of autonomy no human should be considered as a mean towards an end, they are always ends on themselves. Autonomy refers to the individual, not to the community. There is no possible higher good (country, god, science) that can ethically override the free decision and the interest of individuals.

In modern clinical practice, the principle of autonomy is centred on the informed consent of the patient. To consent, the patient must be free of coercion of any type, and able to understand what specifically he or she is given consent for. The right to withdraw the consent at any time is also explicitly recognised.

Two conditions are necessary for the principle of autonomy to be respected: freedom from coercion, and agency, the capacity to bear intentions, understand problems and make decisions. Autonomy is a continuos that varies from full autonomy (good understanding, decision capacity, and freedom) to diverse degrees of non-autonomy.

When agency does not exist, for example in patients with impaired consciousness or small children, or mental disorders; the problem of surrogate autonomy arises. It is the problem of who should decide on behalf of the patient if the patient has lost his or her agency.

Two important rules of conduct derived for the autonomy principle are the following: Do not answer unasked questions. Do not provide unasked help.

Perhaps the most neglected justification of the principle of autonomy is that of the fallibility of the experts. In an specific case it is well known that an expert, “the truly learned”to quote an old ethical code, can make the wrong prediction (the treatment will benefit the patient), while the lay person can make the right prediction (the treatment that generally benefit patients will actually harm this particular one). Despite our hardly won expertise, our costly years of study and efforts to try to understand health problems, despite our more or less successful career, our reputation and authority, we can be wrong and the patient can be right.

Non-maleficence

It is probably the best known of the four principles. Non maleficence means not to harm the patient. This principle refer to the intention of the doctor towards the patient and to the aim of the intervention planned. It is not, of course about the outcome. Otherwise, this central ethical principle will be unhonoured with every adverse event after medical treatment.

It is well known that no doctor can or should guarantee the outcome of a given intervention because it is unknown. For example, the administration of a safe an effective treatment in the right situation, let say penicillin for streptococci infection, have resulted in the death of the patient due to anafilaxia. The doctor, through the correct prescription, caused irreparable harm to the patient. However, from the ethics point of view that act is not unethical.

Beneficence

Beneficence means to do good to the patient. Balancing the benefits, risks, and costs. To do good to the particular, individual patient. As all other overriding principles refers to the individual, not to the patients in plural, even less to any future patients.

Justice

Justice is to give everyone what is due. The principle of justice states that medical benefits should be dispensed fairly, so that people with similar needs and in similar circumstances will be treated with fairness, an important concept in the light of scarce resources.

The principle of justice does not specify what is fair, nor does define any criteria about what fairness means. The ethical principle of justice, which refers to individual patients, is sometimes at odds with the health system and the sociopolitical context. There are two contradictory ways to understand this fairness criteria when providing health services. (1) All resources available to everyone in need, that is, equality of outcome. Regardless any other circumstance (nationality, insurance, income, etc.) everyone receives equal care. (2) Free exchange of medical services. People are free to offer and receive health care. It is equality before law, rather than equality of outcome.

In real life, health care looks like a mixture of the two options in most societies, there is significant room for mixed system. For example in systems (2) there is usually consensus to provide some decent minimum level of health care for all citizens, regardless of ability to pay.

The moral dilemas of the free exchange system are clear enough, poor people receive worse care when compared with the wealthy. It is also arguably true that system (1) is based in some sort of coercion since a part of society must unwillingly cover the expenses of another perhaps to the cost of their own.

Anyway, it is important to distinguish justice in biomedical ethics from the same concept as discussed in the socio-political arena. In biomedical ethics we focus our attention on the individual patient and on the available resources.

Ethics of Innovation

Innovation is at the core of human progress. At the dawn of human history innovation used to be a rare event, most people lived and die doing things in the same way as their ancestors many generation away. By contrast, if we examine our personal history, we will discover that there is barely anything that we do in the same way as our parent or grand parents. Since the Industrial Revolution and the spread of trading around the world, innovation has increased exponentially.

The process of innovation is one of trial and error; we imaging (or copy) new ways of doing thing, we try them out and see what happens. Innovation requires freedom (to innovate) and is the source of wealth, progress, and better outcomes in medicine. But innovation is not without risks and changes looking at improving things might actually results in the opposite.

Because it is difficult to predict a priori the result of an innovation, and because innovators are falible and potential human suffering is involved; in the field of human medicine a system of restriction of the freedom of the innovator and oversight over them should be establish. Specially in medicine, innovation should be ethically responsible.

According to Prof. Marike Brokman, “responsible innovation is actually a moral obligation of surgeons”. It is a practice that departs from the standard, and active search for improvement. In surgery the innovation consist either, on a new implementation of a known treatment (a new indication of a known surgical procedure) or, a technique developed elsewhere. But what exacly constitutes standard practice and what is innovation is far from been clear and there is a lack of standardisation of the definitions.

Even when the innovative technique has been safely tested in another center or by another surgeon, patients might be exposed to increased risks and unforeseen complication especially during the learning curve. Given that the risks associated with the initial learning process are partially unknown, informing patients and obtaining consent might be challenging and it is controversial whether the consent provided is truly informed.

McKneally proposed in 2005 a structured 6 steps protocol that may help to enabling surgical innovation in a rational way: (1) The surgeon writes an enabling innovation letter to the chief specifying the rational for the new technique, and the names of two colleagues that endorse the technique. (2) The so called “Columbus Clause” should be added to the informed consent form stating: “I understand that this treatment is new to this hospital. I will be one of the first [x] patients to receive it here. I have been offered the standard treatment. My doctors and nurses are working to find the best way to perform the new treatment and learn which patients will benefit most from it.’’ (3) If needed, the chief consult other practitioners in the institutional innovation task force including nurses, engineers, ethics, anesthesiologists, etc. (4) The project is presented to the chair of the ethics committee. (5) The innovator reports the results of the first patients. (6) Formal research is initiated if appropriate.

Ethics of Research

The most important document regarding ethics of medical research involving humans is the Declaration of Helsinki issued by the World Medical Association, adopted for the first time in 1964, and reviewed many times. The last version was released in 2013.

The Declaration of Helsinki includes research involving human subjects, and research on identifiable human material and data. It is informed by the following binding statement of medical ethics which every physician must agree upon: “The health of my patient will be my first consideration”, and “a physician shall act in the patient’s best interest when providing medical care”.

The Declaration acknowledges that medical progress is based on research in humans and that the purpose of medical research is to generate new knowledge. However, it is also stated that this goal of generating knowledge can never take precedence over the rights and interests of individual research subjects.

No individual capable of giving informed consent can be enrolled in a research study unless he or she freely agrees. If it cannot be avoid, subjects unable to give consent can be included in medical research. For those, for example comatose patients, the physician must seek informed consent from the legally authorised representative.

The responsibility for the protection of research subjects must always rest with the physician. No national or international ethical, legal or regulatory requirement should reduce or eliminate any of the protections for research subjects set forth in the Helsinki declaration.

Physicians who combine medical research with medical care should involve their patients in research only when participation in the research study will not adversely affect the health of the patients who serve as research subjects.

Discussion: The Evils of Biomedical Ethics

For the discussion of the wrongdoings in biomedical research we could consider two different scenarios:

First, what is good and wrong is obvious and clearly manifested in a set of principles and values accepted by every human being. Every breach of those principles is equally obviously unethical.

Second, it is not always obvious what is good and wrong. To better understand morality we should constantly criticise our proposed solution to ethical dilemas. The corpus of ethical knowledge informs that rational criticism and is actualise by it. In this scenario ethical knowledge is not static, it is ever growing and susceptible to error and improvement.

It is clarifying to analyse the three cases presented at the beginning of the article from the perspective of the second scenario. From this perspective, those crimes were a consequence of the implementation of a wrong ethics. Rather than been only a breach on the ethical principles, they encompassed the creation of new mistaken solution to ethical problems.

Why is that distinction important? because the same wrong solutions to ethical dilemas, perhaps with less catastrophic consequences, are still discussed or implemented in today’s clinical practice, innovation, and research.

Evil 1: Relativism

Relativism is a widespread philosophical position that encompasses several related ideas, but at its core, it refers to the belief that truth, morality, or knowledge is not objective but subjective, relative to individuals, cultures, historical contexts, or other circumstances. What is good or wrong is on the eyes of the beholder, there is no way to say if a moral assertion is correct or mistaken. The relativist states “there is no good, no wrong, all depends on the perspective”.

Moral relativists argue against the existence of objective moral principles. For them the codes of ethics, are an instantiation of this vocation of universal objective morality. This universal moral is opposed to the idea of moral diversity. Relativism is not the sole opposition to the idea of an objective morality, the more common is perhaps skepticism, the view that there is no moral knowledge posible. Skepticism is not discussed here as one of “the evils” because is self-defeating; skeptics are skeptics about their skepticism.

An example of relativistic approach to the biomedical research ethics would be that the criteria for obtaining consent from the subject of research would depend on their special cultural condition. For population where individual freedom is limited, the consent could be surrogated to an authority. In this way the suppression of the autonomy of the individual is justified for the alleged values of the culture, law, or society. Recently, this relativistic justification was implemented by researchers in south France (see Science, Vol 383, Issue 6687). Several published papers in high impact journal were retracted in 2024 for alleged data fabrication, lack of informed consent in specially vulnerable population, and other felonies. The authors argued that in France the law does not obliged researchers to obtain informed consent in some retrospective studies. However, as we have discussed, the Helsinki declaration overrides any national law in the biomedical field.

In 1947, on the occasion of the United Nations debate about universal human rights, the American Anthropological Association issued a statement declaring that moral values are relative to cultures and that there is no way of showing that the values of one culture are better than those of another. That is the clearest apology of the relativistic ethic I know of.

I do not see any harm about applying a relativistic philosophy to the appreciation of art, sport, food, or vacation destinations. That is a matter of taste, the truth of those important issues may be well been on the eyes of the beholder. I confess that to me, relativistic philosophy is always bad philosophy. However, when the same philosophy is implemented in biomedical research, that noble activity can give rise to the worst crimes of the human recorded history.

In 2008, for example, the WHO/UN published a joint statement calling for the “eradication” of female genital mutilation (FGM) (WHO/UN 2008); four years later, the UN passed a unanimous resolution effectively “banning” the practice all around the world. In both cases, the policies were justified, at least in part, by an appeal to objective or universal moral principles, typically expressed in the language of human rights. Critics argued that the prevailing moral discourse surrounding FGM has not been entirely objective, but has instead been compromised by what they see as Western ethnocentrism and cultural imperialism. According to these critics, forbidding the mutilation of girls is not objectively wrong, but a bias of Western culture.

In case one and two (presented at the beginning of this article) relativism is clearly implemented, what is acceptable for the black and poor men (deciding, denying information, and medical care) is not for others. In the second case relativism is also implemented in many different ways, while procreation is encourage for the ones is suppressed for others.

The problem of due obedience (“I was just following orders”), that is manifest in case two, was solved by Immanuel Kant: whenever we are faced with a command by an authority, it is our responsibility to judge whether this command is moral and immoral. The authority may have power to enforce its commands and we may be powerless to resist. But unless we are physically prevented from choosing the responsibility remains ours. It is always our decision whether to obey a command, whether to accept authority.

Evil 2: Utilitarianism

The ethical theory that evaluates actions based on their consequences, particularly the amount of happiness or pleasure they produce. At its core, utilitarianism asserts that the morally right action is the one that maximises overall happiness or utility for the greatest number of people. It does not prioritize the happiness of any particular individual or group but seeks to maximize overall happiness or utility, regardless of personal biases or preferences.

Utilitarianism applied to other than biomedical research on humans in not necessary evil, it seems to be the alleged guiding force of many political decisions. Should a country invest taxpayers money in education of children or in new route connecting cities?

Never the less, when utilitarian philosophy and its ethics correlates are applied to biomedical research the results are catastrophic. It was, for example, the central part of the ethical justification of the Tuskegee experiment, and of the series of medical experiment carried out in war prisoner during the WWII. In both cases, avoidable suffering of humans was justified by a greater good, that of science and that of the nation. This same utilitarian ethics is well alive in today’s discussion as illustrated in case 3. In that case the greater good of a technique or a surgical field is mistakenly weighted in the equation that correspond to the principle of beneficence. Beneficence does never refer to a surgical of technique but to the individual unique patient.

Conclusion

We cannot leave ethics of biomedical research to our intuition or personal beliefs. We can be easily misled by relativistic or utilitarian principles that might be legitimate in other facets of our life. Our work as researchers must be informed by the crimes of the past and especially by the lessons that have arisen from them in the form of ethical codes. Ethics of biomedical research is dynamic, well alive and growing from everyday challenges. Our most precious tools are the unrestricted respect for human individuals and their freedom, the recognition that as researcher we are prone to error in recognising and solving ethical problems, modesty and anti-dogmatism must be the approach to every new challenge. It is imperative to be well familiarised with relativism and utilitarianism and the consequence of their implementation in biomedical research.

References

As quoted, I took some illustrations and information for wikipedia entries about the Nuremberg doctor’s trials and the Tuskegee Study.

M. L. D. Broekman (ed.), Ethics of Innovation in Neurosurgery, Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019.

Ahmed Ammar and Mark Bernstein Editors. Neurosurgical Ethics in Practice: Value-based Medicine. Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London.

Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA. 2000 May 24-31;283(20):2701-11. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.20.2701. PMID: 10819955.

Abecassis IJ, Sen R, Kelly CM, Levy S, Barber J, Ghodke B, Levitt M, Kim LJ, Sekhar LN. Clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness analysis for the treatment of basilar tip aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019 Dec;11(12):1210-1215. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-014747. Epub 2019 Jun 25. PMID: 31239332.

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF (2019) Principles of biomedical ethics, 8th edn. Oxford University Press Inc, New York.

Link to the Declaration of Helsinki: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

Link to the Belmont Report: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/index.html

Loew F. Ethics in Neurosurgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) (1992): 116:187 - 18.

Garfield J. Ethico--legal aspects of high risk neurosurgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992;118(1-2):2-6. doi: 10.1007/BF01400720. PMID: 1414525.

Thomas R. McCormick. Principles of Bioethics: https://depts.washington.edu/bhdept/ethics-medicine/bioethics-topics/articles/principles-bioethics

McKneally MF. The ethics of innovation: Columbus and others try something new. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011 Apr;141(4):863-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.01.003. PMID: 21419897.

American Medical Association. Original Code of Medical Ethics, 1847. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/public/ethics/1847code_0.pdf

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-relativism/

Earp BD. Between Moral Relativism and Moral Hypocrisy: Reframing the Debate on "FGM". Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2016 Jun;26(2):105-44. doi: 10.1353/ken.2016.0009. PMID: 27477191.

Karl R. Popper. Conjectures and refutations. Routledge.

The reckoning. Didier Raolt and his institute found fame during the pandemic. Then, a group of dogged critics exposed major ethical failings. Science, Vol 383, Issue 6687.