The short answer to the question of the title is that we can improve our practice by learning from our mistakes. The longer answer will inevitably address the question of how do we learn, how does our knowledge grows: that is the epistemological question, the study of the process of learning.

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that studies the production of knowledge, how do we know, what can be know, and where does knowledge comes from. It study the methodology of science and also tho the others areas of human knowledge. Epistemology applies particularly well to 'pure sciences,' such as theoretical Physics, Chemistry, or Biology, but it must also cover the study of all forms of knowledge, including scientific disciplines such as Medicine. What is the source of knowledge, and how does it grow? These are the central questions of epistemology.

There have been a number of successful neurosurgeons over the years. They all started their careers presumably knowing close to nothing and lacking basic skills. How did they learn? I was privileged to learn from one of those surgeons, Prof Juha Hernesniemi, when he was at the peak of his career. He held the key to the answer to the question: How do we improve or practice? However, I doubt (but I also don't know) whether he had an explicit and clear idea about his method for learning.

I observed his surgeries: they were quick, clean, and effective—in other words, perfect. But once the surgery finished and the fellow was closing up, he would join us (the visitors) on the bench he had kindly set up in the operating room. He would not comment on the effective strategy and precise execution, nor would he talk about the beauty of his craft. He would only talk about the mistakes he had just made, which were, up to that moment, invisible to us.

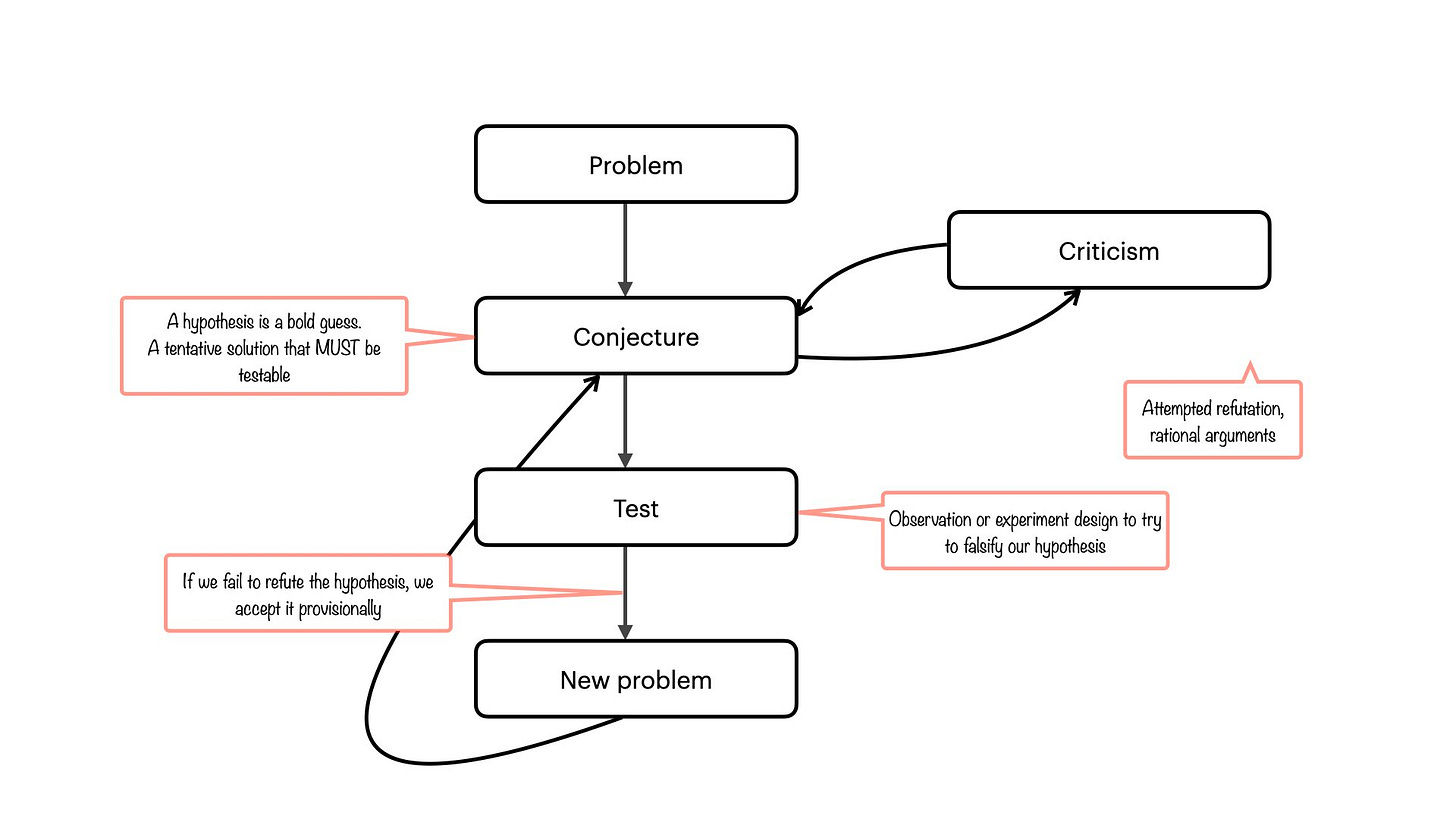

The most advanced theory of knowledge (epistemology) is based on a simple idea: we can only learn from our mistakes. The philosopher Karl Popper fully characterized the scientific method and provided the most comprehensible review of the theory of knowledge. According to Popper, the only way to make knowledge grow is through trial and error. The process can be summarized as follows: we start with problems and then hypothesize possible solutions. Those tentative solutions are controlled and refined through several rounds of criticism. Then we direct our attention to reality to test, check, observe, collect data, and conduct experiments. Serious criticism, observation, or experimentation involves attempted refutation. We try hard to prove ourselves wrong. If we fail to refute our hypothesis, if we fail to prove ourselves wrong, then we might have solved the problem, for the moment at least. And when we solve the problem, new and better problems will arise, and our knowledge will expand. The process repeats itself ad-infinitum; there is no definitive solution to a problem. The possibility of perfection has not been granted to us fallible humans.

Here is in, a nutshell, Popper’s theory of knowledge according to Popper:

“[…] we can learn from our mistakes.

It is a theory of reason that assigns to rational arguments the modest and yet important role of criticizing our often mistaken attempts to solve our problems.

And it is a theory of experience that assigns to our observations the equally modest and almost equally important role of tests which may help us in the discovery of our mistakes. Though it stresses our fallibility it does not resign itself to scepticism, for it also stresses the fact that knowledge can grow, and that science can progress just because we can learn from our mistakes.

The way in which knowledge progresses, and especially our scientific knowledge, is by unjustified (and unjustifiable) anticipations, by guesses, by tentative solutions to our problems, by conjectures [hypothesis]. These conjectures are controlled by criticism; that is, by attempted refutations, which include severely critical tests. They may survive these tests; but they can never be positively justified: they can be established neither as certainly true nor even as 'probable' (in the sense of the probability calculus). Criticism of our conjectures is of decisive importance: by bringing out our mistakes it makes us understand the difficulties of the problem which we are trying to solve. This is how we become better acquainted with our problem, and able to propose more mature solutions: the very refutation of a theory- that is, of any serious tentative solution to our problem- is always a step forward that takes us nearer to the truth. And this is how we can learn from our mistakes.

As we learn from our mistakes our knowledge grows, even though we may never know-that is, know for certain. Since our knowledge can grow, there can be no reason here for despair of reason. And since we can never know for certain, there can be no authority here for any claim to authority, for conceit over our knowledge, or for smugness.

Those among our theories which turn out to be highly resistant to criticism, and which appear to us at a certain moment of time to be better approximations to truth than other known theories, may be described, together with the reports of their tests, as 'the science' of that time. Since none of them can be positively justified, it is essentially their critical and progressive character- the fact that we can argue about their claim to solve our problems better than their competitors-which constitutes the rationality of science.”

These ideas emphasize the central role of errors, mistakes, and complications in learning neurosurgery and anything else. They also underscore the importance of modesty (the fact that we recognise our tendency to do mistakes), of creative thinking and imagination, as they are the sole sources of our tentative solutions, guesses, and hypotheses.

Let me state this important fact again: modesty, the recognition that we do fail, is a necessary condition for learning for improving or practice.

However, this fact might conflict with many aspects of our everyday practice, training, and teaching. Due to the potential for human suffering, while one can and must celebrate a clarifying error in an abstract experiment or in the lab, it would be unethical to do so in the case of a surgical complication . The primary concern of every surgeon is to avoid complications, and the only way to approaching that aim is by learning from them. By doing so, we contribute to the growth of our collective knowledge. In this sense, hiding or disregarding complications is not only dishonest and unethical, but it also hinders the progress of the field.

We learn from our own and others' complications, mistakes, and suboptimal results on the one hand, and on the other, we must strive to avoid them. Constant learning is still possible because every surgeon is fallible, and mistakes are ubiquitous. There is no such thing as perfect practice, technique, or surgery. There are always things to be improved, and it is in those areas that we should focus our attention.

The fact that we can only learn from our own and others' mistakes contrasts harshly with certain training or teaching strategies, where neurosurgery is presented as a collection of perfect, spotless procedures. No complications to report, just perfect results. It might seem paradoxical, but true learning is hindered when the pitfalls are hidden. No matter the noble intentions of the teacher, such practices are more suited for self-promotion, and I suspect that in some cases, that's what it might truly be: self-advertising disguised as teaching. Teaching strategies built upon the presentation of allegedly flawless practices are not only deceptive, but they are also ineffective.